| Home -> Other Books -> Storied Walls of the Exposition -> Chapter 3 - Symbolism | |||

|

Chapter III

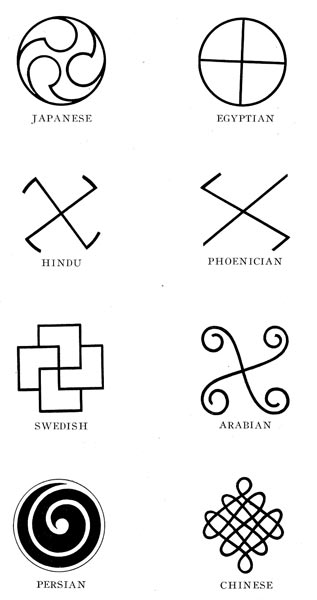

Symbolism Because of the lavish freedom of its decoration, Spanish architecture yields broad opportunity to architect and artist for the use of symbolism - the expression of a thought by conventional figures or conventionalized forms. In this freedom the builders of the Exposition have reveled. In their use of symbolic emblems at the Exposition the architects have chosen many that have a direct and definite meaning. These they have combined with decorative motives of their own in producing a most original and charming and beautiful effect. For some of the symbols used they have drawn upon the architectural history of the ages. In many cases these have been adapted almost in their primitive form. In others they have been much conventionalized, but under either the original or the conventional use of these old forms, their meaning will be revealed to those "who see with the eyes of the soul." Some of these emblems are most complicated; some are very simple; some drawn from pagan sources; some from the Christian. Some have evidently been used without thought of their meaning, and for decoration only; others have been carefully chosen to give form to the thought that underlay the architect's work. But around them all hangs the mystic charm of the cipher and the secret, the story that is revealed only to him whose eyes have been opened by a love of the beautiful and whose mind is enriched with the lore of buried years. Symbolism may be best and most simply defined as a sign for the thing signified; a suggestion for the idea. It has had its forms in every phase of human nature and intelligence. In art and architectural decoration it has two distinct trends - one religious, the other intellectual - and in the Orient and in the Occident its expression has differed widely in purpose. In the Orient it became involved in the thought of mystery, reserve, aloofness; its purpose mainly religious its meaning veiled to all but the initiate; its tendency to conceal. In the Occident it appealed more to the growing intelligence, seeking freer and larger modes of expression, and its purpose was to reveal. At first it was an effort at a direct message, generally religious in intent. Later it became a beautiful and varied scheme of decorative effect. As time went on the desire to impart deeper meanings led to such complexity that symbolism rose above the comprehension of the masses. Its messages became as a sealed book, especially in the Orient. Primitive man, essentially a social animal, desired communication with his fellows. At first by signs was the gulf bridged. Then came the crude sound ripening into the spoken word later the picture, often merely an outline, first drawn in the dust or on the sands of the shore, and later chiseled into the cliff, bearing its message of warning or of vengeance. Then a spot of crimson, the feather of a bird or an autumn-colored leaf was laid near by, that the eye might be caught by the glow of color, and so decoration entered into the kingdom of art and went hand in hand with it down through the ages. Thus had symbolism its beginning in these two great phases of decorative or didactic purpose. Last of all came man's supreme intellectual achievement - the use of a symbol for each vocal sound - the alphabet. Then the signs of weights, measures, and values came, and with these at hand to communicate thought, symbolism as a spiritual or religious mode of expression fell into decay. It was revived again in the early days of Christian art, but once more, inspired by religious purpose, it took on the old mystic phase which shut it eventually from the understanding of the illiterate for whose information it had been revived. Thus defeating itself it perished for a time from the world of art, to be revived again in new splendor and beauty and power through the Renaissance, coming into its kingdom again as a beautiful decorative motive, employed not only in painting but in architecture and sculpture. It is in this last phase of its use that it finds expression today. The earliest known or most primitive of symbolic characters is perhaps the swastika, found in some form in every land. The Japanese swastika is composed of curves; the Chinese has a series of squares centering around a common point; the Hindu radiates from a center. The form appears in the Greek and Roman fret and is seen in the mystic Egyptian sign of death across the wings of the scarab. This is a symbol of eternity, line returning upon line. From the Egyptians the Greeks drew many inspirations in their art, and from the earliest times they employed symbols, some acquired from other lands and some evolved by themselves. From the Greeks come most of the flower symbols, the symbols of the seasons and of the heavenly bodies. There was nothing mysterious or threatening in their thought. The more mystic power which the Egyptian symbolism possessed seemed to the Greeks to threaten rather than to invite, and in adapting these forms the Greeks stripped them of much of this sinister suggestion. The Greeks had not many animal symbols, leaving these to the Hindus, the Chinese, the Japanese and the Romans. Symbols of the forces of nature the Egyptians shared with the Greeks, but it remained for the latter to develop these into motives of singular beauty and definite meaning. While the Egyptians preceded the Greeks in the use of these nature symbols, with them these forms were crude and never very highly developed. In China, Japan and India symbolism grew so complicated that it became exaggerated into the grotesque, and the temples and tombs of these lands were peopled with strange monsters of terrifying aspect. As animal life to these races was intensely sacred, their symbolism principally tended towards the exploitation of animal forms, but varied by the adaptation of nature forms the curves of a river to suggest overflow; the triangular sign of the mountain to denote a barrier; or the zigzag line suggesting a man-made road. Undoubtedly from the Orient and the Egyptians the Romans took their early modes of symbolic expression. They gave to animal forms in a more material way, the symbolic meaning of the various powers that they themselves held in high esteem - strength to the lion, speed to the eagle, craft to the fox. The Persians, worshipers of the sun and of fire, and perhaps deriving from their Assyrian and Babylonian ancestors the underlying thought of some great and all-powerful controlling force, used the theme of light as opposed to darkness. To them the sun was most sacred and the things made by man but of little purpose. It was not right in their philosophy of life that the works of God should be copied by man, and so their symbolism has a strange fantastic trend. Their animal, their tree, their mountain and their river signs were deliberately distorted. The only one easily read and easily understood is the beautiful sun-ray cipher - beams of light radiating from a central force. It is a strange fact that in their employment of nature signs and in their reverential attitude toward the great forces of nature, the Aztec Indians and the American Indians employed their symbolic expressions in the same general way as the Egyptians and the Persians. At the beginning of the Christian era the world found itself with an intellectual capacity superior to its ability for expression and the transmission of knowledge. The story of the birth, life and death of Christ spread rapidly from man to man, its pathos and dramatic power making a direct appeal. When persecution began it became necessary to practise the new faith in secret. Its story could not be written as few among its followers dared carry the scroll, and the masses moreover knew not how to read, therefore it was told symbolically, secretly. The life of Christ lends itself marvelously to pictorial expression, and in the early days of Christianity artists had recourse to the ancient method of giving their message through visible signs. Because of its peculiar personal appeal, the human being was first used as a medium of expression. Well-known figures became associated with definite thoughts and meanings. Later, in place of a definite personality, it became expedient to identify the figure by some conventional sign or symbol, as Saint Mark with a lion, Saint Sebastian with arrows. Still later, in the days of persecution, and the necessity for greater secrecy, merely the sign - the lion or the arrow - was used. That the full meaning might be given, the words necessary to an interpretation of a picture were often printed on scrolls held in the hands, or issuing from the mouths of the figures. As persecutions grew more violent these also were abandoned and the cross, the crown, the palm, the heart of flames or the fish stood alone, and "to the eyes of the soul" full of a deep and definite meaning. When Christianity was established as a national creed and an open avowal of belief was safe, the beautiful story entered into pictorial art and gave to us the best of the high Renaissance in Italy - a period of classic perfection, unapproachable, unsurpassed. Art at this teeming period drew upon the resources of all ages, all races, all times. It drew for its motives in decoration or in expression upon the pagan as well as the Christian, the Orient as well as the Occident, upon the material as well as upon the spiritual, and it wrought into one harmonious whole the intellectual thought that had run beside the outward sign throughout the centuries. In the same cosmopolitan spirit has symbolism been given to us here today - not on canvas, not in marble, but upon the roofs, the domes, the doors, the cornices, the friezes, arches and portals in this Dream City. Symbolism of today while sacrificing nothing of the sentiment or mysticism of the earlier symbolism, has added to them a note of materialism peculiar to modern times. In its materialistic form modern symbolism has lost none of its decorative splendor or importance, and the builders of the Exposition have made lavish use of this peculiar value. There are definite examples of this in the Miner with his pick at the door of the Varied Industries Palace, contrasted as it is with the Rose of Old Spain, the Cross of the Crusader, the Angel with the Key, the Flaming Torch and the Shell, all belonging to the earlier days of symbolistic usage. In the End of the Trail the realistic story of desolation, defeat and despair is in contrast with the old Renaissance decorations in the Court of Palms behind it. Realism appears again in the splendid figures of Power, Electricity, Steam and Invention, and in the sphinxlike figures of Machinery bound in the chains of its own making, as they are found at the great Roman doorway of the Machinery Palace. Again it is on the Marina where the Bowman gives the definite symbol - Energy, Ambition, Success. And he stands in the midst of the most complex symbolism of all, the symbolism of old Spain with its mysticism and its background of classic and Oriental lore, shown in the four main doorways fronting the bay. It is this constant contrast that makes the symbolism of the Exposition so fascinating and so well worth study.

|

|||